The Franks Casket Right Side Again

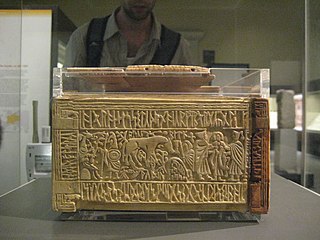

The Franks Casket, as displayed in the British Museum; the front end and lid

The Franks Casket (or the Auzon Casket) is a small Anglo-Saxon whale's os (not "whalebone" in the sense of baleen) chest from the early 8th century, now in the British Museum. The catafalque is densely decorated with pocketknife-cut narrative scenes in apartment two-dimensional low-relief and with inscriptions mostly in Anglo-Saxon runes. Generally thought to exist of Northumbrian origin,[1] information technology is of unique importance for the insight it gives into early Anglo-Saxon fine art and civilization. Both identifying the images and interpreting the runic inscriptions has generated a considerable amount of scholarship.[two]

The imagery is very various in its subject matter and derivations, and includes a single Christian epitome, the Admiration of the Magi, along with images derived from Roman history (Emperor Titus) and Roman mythology (Romulus and Remus), too every bit a depiction of at least one legend ethnic to the Germanic peoples: that of Weyland the Smith. It has as well been suggested that there may be an episode from the Sigurd legend, an otherwise lost episode from the life of Weyland's brother Egil, a Homeric legend involving Achilles, and perhaps even an allusion to the legendary founding of England by Hengist and Horsa.

The inscriptions "display a deliberate linguistic and alphabetic virtuosity; though they are more often than not written in One-time English and in runes, they shift into Latin and the Roman alphabet; so back into runes while nevertheless writing Latin".[3] Some are written upside down or dorsum to front.[four] It is named after a sometime owner, Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks, who gave information technology to the British Museum.

History [edit]

A monastic origin is generally accepted for the casket, which was perhaps fabricated for presentation to an important secular effigy, and Wilfrid's foundation at Ripon has been specifically suggested.[5] The postal service-medieval history of the catafalque earlier the mid-19th century was unknown until relatively recently, when investigations by Westward. H. J. Weale revealed that the casket had belonged to the church of Saint-Julien, Brioude in Haute Loire (upper Loire region), France; it is possible that it was looted during the French Revolution.[vi] It was and then in the possession of a family unit in Auzon, a hamlet in Haute Loire. It served every bit a sewing box until the silver hinges and fittings joining the panels were traded for a silver ring. Without the support of these the casket fell apart. The parts were shown to a Professor Mathieu from nearby Clermont-Ferrand, who sold them to an antique shop in Paris, where they were bought in 1857 by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks, who subsequently donated the panels in 1867 to the British Museum, where he was Keeper of the British and Medieval collections. The missing correct cease panel was later found in a drawer by the family in Auzon and sold to the Bargello Museum, Florence, where it was identified as part of the casket in 1890. The British Museum brandish includes a cast of information technology.[7]

Description and interpretations [edit]

The casket is 22.9 cm long, xix cm wide and 10.9 cm high – nine × 7+ 1⁄2 by five+ 1⁄eight inches, and can be dated from the language of its inscriptions and other features to the first half of the eighth century Advertisement.[8] There are other inscriptions, "tituli" identifying some figures that are not detailed beneath and appear within the image field. The mounts in precious metal that were undoubtedly originally nowadays are missing, and it is "likely" that it was originally painted in color.[nine]

The breast is clearly modelled on Tardily Antique ivory caskets such every bit the Brescia Catafalque;[ten] the Veroli Catafalque in the Five&A Museum is a Byzantine interpretation of the style, in revived classical mode, from virtually thou.[eleven]

Leslie Webster regards the casket as probably originating in a monastic context, where the maker "clearly possessed neat learning and ingenuity, to construct an object which is and then visually and intellectually complex. ... it is generally accustomed that the scenes, drawn from contrasting traditions, were carefully chosen to counterpoint one another in the creation of an overarching set of Christian messages. What used to be seen equally an eccentric, almost random, assemblage of heathen Germanic and Christian stories is now understood as a sophisticated programme perfectly in accord with the Church building's concept of universal history". It may accept been intended to hold a volume, perhaps a psalter, and intended to be presented to a "secular, probably royal, recipient"[12]

Front end panel [edit]

The front panel, which originally had a lock fitted, depicts elements from the Germanic legend of Wayland the Smith in the left-hand scene, and the Adoration of the Magi on the right. Wayland (besides spelled Weyland, Welund or Vølund) stands at the extreme left in the forge where he is held as a slave by King Niðhad, who has had his hamstrings cut to hobble him. Below the forge is the headless body of Niðhad's son, whom Wayland has killed, making a goblet from his skull; his caput is probably the object held in the tongs in Wayland's mitt. With his other mitt Wayland offers the goblet, containing drugged beer, to Beaduhild, Niðhad's girl, whom he then rapes when she is unconscious. Another female person effigy is shown in the center; perhaps Wayland's helper, or Beaduhild again. To the right of the scene Wayland (or his brother) catches birds; he and so makes wings from their feathers, with which he is able to escape.[13]

In a sharp dissimilarity, the right-manus scene shows one of the most common Christian subjects depicted in the art of the period; however here "the birth of a hero besides makes good sin and suffering".[14] The Iii Magi, identified past an inscription (ᛗᚫᚷᛁ, "magi"), led by the large star, approach the enthroned Madonna and Child bearing the traditional gifts. A goose-similar bird by the feet of the leading magus may correspond the Holy Spirit, commonly shown equally a dove, or an angel. The human figures, at least, form a limerick very comparable to those in other depictions of the period. Richard Fletcher considered this dissimilarity of scenes, from left to right, every bit intended to indicate the positive and beneficial effects of conversion to Christianity.[15]

Around the panel runs the post-obit alliterating inscription, which does non relate to the scenes but is a riddle on the cloth of the casket itself as whale os, and specifically from a stranded whale:

| transcription of runes | transliteration of runes | standardised to Late West Saxon | possible translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ᚠᛁᛋᚳ ᛫ ᚠᛚᚩᛞᚢ ᛫ ᚪᚻᚩᚠᚩᚾᚠᛖᚱᚷ ¶ ᛖᚾᛒᛖᚱᛁᚷ ¶ ᚹᚪᚱᚦᚷᚪ ᛬ ᛋᚱᛁᚳᚷᚱᚩᚱᚾᚦᚫᚱᚻᛖᚩᚾᚷᚱᛖᚢᛏᚷᛁᛋᚹᚩᛗ ¶ ᚻᚱᚩᚾᚫᛋᛒᚪᚾ | fisc · flodu · ahofonferg ¶ enberig ¶ warþga : sricgrornþærheongreutgiswom ¶ hronæsban | Fisc flōd āhōf on firgenberig. Wearþ gāsric(?) grorn þǣr hē on grēot geswam. Hranes bān. | The flood bandage up the fish on the mountain-cliff The terror-king became sad where he swam on the shingle. Whale's os.[16] |

Left console [edit]

The left panel depicts the mythological twin founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, being suckled by a she-wolf lying on her back at the lesser of the scene. The same wolf, or another, stands to a higher place, and there are two men with spears approaching from each side. The inscription reads:

| transcription of runes | transliteration of runes | standardised to Tardily West Saxon | possible translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ᚱᚩᛗᚹᚪᛚᚢᛋᚪᚾᛞᚱᛖᚢᛗᚹᚪᛚᚢᛋᛏᚹᛟᚷᛖᚾ ¶ ᚷᛁᛒᚱᚩᚦᚫᚱ ¶ ᚪᚠᛟᛞᛞᚫᚻᛁᚫᚹᚣᛚᛁᚠᛁᚾᚱᚩᛗᚫᚳᚫᛋᛏᚱᛁ ᛬ ¶ ᚩᚦᛚᚫᚢᚾᚾᛖᚷ | romwalusandreumwalus twœgen ¶ gibroðær ¶ afœddæhiæ wylifinromæcæstri : ¶ oþlæunneg | Rōmwalus and Rēomwalus, twēgen gebrōðera: fēdde hīe wylf in Rōmeceastre, ēðle unnēah. | Romulus and Remus, 2 brothers, a she-wolf nourished them in Rome, far from their native land.[17] |

Carol Neuman de Vegvar (1999) observes that other depictions of Romulus and Remus are found in East Anglian art and coinage (for example the very early Undley bracteate).[18] She suggests that because of the similarity of the story of Romulus and Remus to that of Hengist and Horsa, the brothers who were said to take founded England, "the legend of a pair of outcast or traveller brothers who led a people and contributed to the formation of a kingdom was probably not unfamiliar in the 8th-century Anglo-Saxon milieu of the Franks Casket and could stand up as a reference to destined rulership."[nineteen]

Rear panel [edit]

The rear panel depicts the Taking of Jerusalem past Titus in the Get-go Jewish-Roman War. The inscription is partly in Old English and partly in Latin, and part of the Latin portion is written in Latin letters (indicated below in upper case letters), with the residuum transcribed phonetically into runic messages. Two isolated words stand in the lower corners.[20]

At the centre of the panel is a depiction of a building, probably representing the Temple of Jerusalem.

In the upper left quadrant, the Romans, led by Titus in a helm with a sword, assault the primal building. The associated text reads 'ᚻᛖᚱᚠᛖᚷᛏᚪᚦ | ᛭ᛏᛁᛏᚢᛋᛖᚾᛞᚷᛁᚢᚦᛖᚪᛋᚢ' (in Latin transliteration herfegtaþ | +titusendgiuþeasu, and if normalised to Tardily W Saxon 'Hēr feohtaþ Tītus and Iūdēas'): 'Here Titus and the Jews fight'.

In the upper right quadrant, the Jewish population abscond, casting glances backwards. The associated text, which is in Latin and partly uses Latin letters and partly runes, reads 'HICFUGIANTHIERUSALIM | ᚪᚠᛁᛏᚪᛏᚩᚱᛖᛋ' (in normalised Classical Latin: 'hic fugiant Hierusalim habitatores'): 'Here the inhabitants flee from Jerusalem'.

In the lower left quadrant, a seated judge announces the judgement of the defeated Jews, which as recounted in Josephus was to be sold into slavery. The associated text, in the lesser left corner of the panel, reads 'ᛞᚩᛗ' (if normalised to Late Due west Saxon: 'dōm'): 'sentence'.

In the lower right quadrant, the slaves/hostages are led away, with the text, in the bottom right corner of the console, reading 'ᚷᛁᛋᛚ' (if normalised to Tardily West Saxon: 'gīsl'): 'hostages'.

Hat [edit]

The hat of the casket is said by some to depict an otherwise lost fable of Egil; Egil fends off an regular army with bow and arrow while the female person behind him may be his wife Olrun. Others interpret it as a scene from the Trojan War involving Achilles

The hat as it now survives is incomplete. Leslie Webster has suggested that in that location may take been relief panels in silver making up the missing areas. The empty circular surface area in the centre probably housed the metallic dominate for a handle.[21] The lid shows a scene of an archer, labelled ᚫᚷᛁᛚᛁ or Ægili, single-handedly defending a fortress against a troop of attackers, who from their larger size may exist giants.

In 1866, Sophus Bugge "followed up his explanation of the Weland motion-picture show on the front of the casket with the suggestion that the bowman on the top slice is Egil, Weland'due south brother, and thinks that the 'carving tells a story about him of which we know zip. We see that he defends himself with arrows. Behind him appears to sit a woman in a business firm; maybe this may be Egil's spouse Ölrún.'"[22] In Norse mythology, Egil is named every bit a brother of Weyland (Weland), who is shown on the forepart console of the casket. The Þiðrekssaga depicts Egil as a primary archer and the Völundarkviða tells that he was the husband of the swan maiden Olrun. The Pforzen buckle inscription, dating to nigh the same menses as the casket, also makes reference to the couple Egil and Olrun (Áigil andi Áilrun). The British Museum webpage and Leslie Webster concur, the onetime stating that "The lid appears to depict an episode relating to the Germanic hero Egil and has the single label ægili = 'Egil'."[23]

Josef Strzygowski (quoted by Viëtor 1904) proposed instead that the lid represents a scene pertaining to the fall of Troy, merely did non elaborate. Karl Schneider (1959) identifies the word Ægili on the lid as an Anglo-Saxon form of the proper noun of the Greek hero Achilles. As nominative singular, it would signal that the archer is Achilles, while as dative singular it could hateful either that the citadel belongs to Achilles, or that the arrow that is about to exist shot is meant for Achilles. Schneider himself interprets the scene on the chapeau as representing the massacre of Andromache'southward brothers past Achilles at Thebes in a story from the Iliad, with Achilles equally the archer and Andromache's mother held captive in the room behind him. Amy Vandersall (1975) confirms Schneider's reading of Ægili equally relating to Achilles, but would instead accept the lid depict the Trojan attack on the Greek camp, with the Greek bowman Teucer as the archer and the person backside the archer (interpreted as a woman by most other authors) as Achilles in his tent.

Other authors see a Biblical or Christian message in the lid: Marijane Osborn finds that several details in Psalm 90, "especially equally it appears in its Old English language translation, ... may exist aligned with details in the picture on the hat of the casket: the soul shielded in verse 5 and safely sheltered in the ... sanctuary in poetry 9, the spiritual battle for the soul throughout, the flying missiles in verse 6 and an angelic defender in verse 11."[24] Leopold Peeters (1996:44) proposes that the lid depicts the defeat of Agila, the Arian Visigothic ruler of Hispania and Septimania, by Roman Catholic forces in 554 A.D. According to Gabriele Cocco (2009), the lid most likely portrays the story of Elisha and Joas from 2 Kings 13:17, in which the prophet Elisha directs King Joas to shoot an pointer out an open up window to symbolise his struggle confronting the Syrians: "Hence, the Ægili-bowman is Male monarch Joas and the figure nether the curvation is Elisha. The prophet would then exist wearing a hood, typical of Semitic populations, and holding a staff."[25] Webster (2012b:46-viii) notes that the ii-headed beast both above and below the figure in the room backside the archer as well appears beneath the feet of Christ equally King David in an illustration from an eighth-century Northumbrian manuscript of Cassiodorus, Commentary on the Psalms.

Right panel [edit]

The replica correct panel in London

This, the Bargello panel, has produced the most divergent readings of both text and images, and no reading of either has achieved general acceptance. At left an animal effigy sits on a small rounded mound, confronted by an armed and helmeted warrior. In the centre a standing animal, ordinarily seen as a horse, faces a effigy, belongings a stick or sword, who stands over something divers by a curved line. On the right are three figures.

Raymond Folio reads the inscription as

| transliteration of runes | standardised to Late West Saxon | possible translation |

|---|---|---|

| herhos(?) sitæþ on hærmberge ¶ agl? drigiþ ¶ swa hiri ertae gisgraf særden sorgæ ¶ and sefa tornæ risci ¶ wudu ¶ bita | Hēr Hōs siteþ on hearmbeorge: agl[?] drīgeþ swā rent Erta gescræf sār-denn sorge and sefan torne. rixe / wudu / bita | Here Hos sits on the sorrow-mound; She suffers distress equally Ertae had imposed information technology upon her, a wretched den (?wood) of sorrows and of torments of listen. rushes / wood / biter[26] |

Even so, a definitive translation of the lines has met with difficulty, partly because the runes are run together without separators betwixt words, and partly because two letters are cleaved or missing. Every bit an extra challenge for the reader, on the right panel simply, the vowels are encrypted with a elementary substitution cipher. Three of the vowels are represented consistently by three invented symbols. Nonetheless, ii additional symbols represent both a and æ, and according to Folio, "it is not articulate which is which or even if the carver distinguished competently between the two."[27] Reading 1 rune, transcribed by Page and others as r but which is different from the usual r-rune, as a rune for u, Thomas A. Bredehoft has suggested the culling reading

- Her Hos sitæþ on hæum bergæ

- agl[.] drigiþ, swæ hiri Eutae gisgraf

- sæuden sorgæ and sefa tornæ. [28]

- Here sits Hos on [or in] the high hill [or barrow];

- she endures agl[.] as the Jute appointed to her,

- a sæuden of sorrow and troubles of listen.

Page writes, "What the scenes represent I do not know. Excited and imaginative scholars take put forrard numbers of suggestions but none convinces."[29] Several of these theories are outlined below.

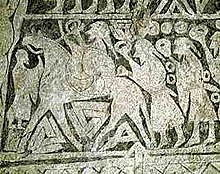

Sigurd and Grani? [edit]

A "Sigurd stone" from eastern Sweden depicts Sigurd's horse Grani.

Elis Wadstein (1900) proposed that the correct console depicts the Germanic fable of Sigurd, known also as Siegfried, existence mourned by his equus caballus Grani and wife Guthrun. Eleanor Clark (1930) added, "Indeed, no ane seeing the figure of the horse bending over the tomb of a man could fail to call back the words of the Guthrunarkvitha (II,v):

- The head of Grani was bowed to the grass,

- The steed knew well his master was slain."[xxx]

While Clark admits that this is an "extremely obscure fable,"[31] she assumes that the scene must be based on a Germanic legend, and tin can find no other instance in the entire Norse mythology of a horse weeping over a dead body.[32] She concludes that the pocket-sized, legless person inside the cardinal mound must be Sigurd himself, with his legs gnawed off by the wolves mentioned in Guthrun's story. She interprets the three figures to the right as Guthrun being led away from his tomb by his slayers Gunnar and Hogne, and the female figure earlier Grani as the Norn-goddess Urd, who passes judgement on the dead. The warrior to the left would then exist Sigurd again, now restored to his former prime for the afterlife, and "sent rejoicing on his way to Odainsaker, the realms of bliss for deserving mortals. The gateway to these glittering fields is guarded by a winged dragon who feeds on the imperishable flora that characterised the place, and the bodyless cock crows lustily equally a kind of eerie genius loci identifying the spot equally Hel'southward wall."[33]

Although the Sigurd-Grani thesis remains the most widely accepted interpretation of the correct panel, Arthur Napier remarked already in 1901, "I remain entirely unconvinced by the reasons [Wadstein] puts frontwards, and believe that the true explanation of the picture has nonetheless to be found."[34]

Hengist and Horsa? [edit]

A.C. Bouman (1965) and Simonne d'Ardenne (1966)[35] instead translate the mournful stallion (One-time English hengist) at the middle of the right console equally representing Hengist, who, with his brother Horsa, beginning led the Onetime Saxons, Angles, and Jutes into Britain, and eventually became the commencement Anglo-Saxon king in England, according to both Bede'southward Ecclesiastical History of the English language People and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The miniature person inside the burial mound he grieves over would then be Horsa, who died at the boxing of Ægelesthrep in 455 A.D. and was buried in a flint tumulus at Horsted near Aylesford. Bouman suggests that the female mourner could then be Hengist's famous daughter Renwein.

Bouman and d'Ardenne identify the strange fauna on the left with the head of a equus caballus, the habiliment and posture of a man, and the wings of a spirit, as Horsa again, this time equally a spirit seated on his own burial mound. Horsa (whose proper name means horse in Quondam English) would then be the "Hos" referred to in the panel's inscription every bit sitting on a "sorrow-mound." They note that there is a miniature horse in each corner of the console, in keeping with its theme of two famous "horses."

The Deity of the Grove? [edit]

Ordinarily herhos sitæþ is read, "here sits the equus caballus". Nonetheless, Wilhelm Krause (1959) instead separates herh (temple) and os (divinity). Alfred Becker (1973, 2002), post-obit Krause, interprets herh as a sacred grove, the site where in pagan days the Æsir were worshipped, and bone as a goddess or valkyrie. On the left, a warrior "has met his fate in guise of a frightening monster... As the consequence, the warrior rests in his grave shown in the middle department. There (left of the mound) we take a horse marked with 2 trefoils, the divine symbols.... Higher up the mound we run across a chalice and right of the mound a woman with a staff in hand. Information technology is his Valkyrie, who has left her seat and come to him in the shape of a bird. Now she is his cute sigwif, the hero'south benevolent, even loving companion, who revives him with a draught from that chalice and takes him to Valhalla. The horse may be Sleipnir, Woden'due south famous stallion."[36]

Krause and Becker phone call attending to the significance of the two trefoil marks or valknutr between the stallion's legs, which denote the realm of death and tin can be found in similar position on picture stones from Gotland, Sweden like the Tängelgårda stone and the Stora Hammars stones. Two other pictures of the Franks Casket bear witness this symbol. On the forepart it marks the third of the Magi, who brings myrrh. Information technology also appears on the lid, where according to Becker, Valhalla is depicted.

The Madness of Nebuchadnezzar? [edit]

Leopold Peeters (1996) proposes that the correct panel provides a pictorial illustration of the biblical Volume of Daniel, ch. 4 and 5: The wild creature at the left represents Nebuchadnezzar after he "was driven away from people and given the mind of an animal; he lived with the wild asses and ate grass like cattle."[37] The figure facing him is and then the "watchful ane" who decreed Nebuchadnezzar's fate in a dream (four.13-31), and the quadruped in the centre represents one of the wild asses with whom he lived. Some of the details Peeters cites are specific to the Old English poem based on Daniel.

According to Peeters, the three figures at the right may then stand for Belshazzar'south married woman and concubines, "conducting blasphemous rites of irreverence (Dan. 5:1-4, 22)."[38] The corpse in the fundamental burial mound would represent Belshazzar himself, who was murdered that night, and the woman mourning him may be the queen mother. The cryptic runes on this panel may be intended to invoke the mysterious writing that appeared on the palace wall during these events.

The Death of Balder? [edit]

David Howlett (1997) identifies the illustrations on the right console with the story of the decease of Balder, as told by the late 12th-century Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum.[39] According to Saxo, Balder's rival Hother meets three women in a chilly wood late at night, who provide him with a chugalug and girdle that volition enable him to defeat Balder. Hother wounds Balder, who dies three days after and is cached in a mound.

Howlett identifies the 3 figures at the correct with the 3 wood maidens (who may exist the 3 Norns), and the shrouded man within the key mound with Balder. "The woman to the correct of the mound is Hel, Saxo'due south Proserpina, prophesying Balder's death and condemning Woden to sorrow and humiliation. The stallion to the left of the mound is Balder'due south father Woden."[twoscore] In Saxo's story, Woden then begets a second son, Boe (Bous or Váli), to avenge Balder's death. Howlett interprets the warrior at left as Boe, and "ane infers that the mound is depicted twice and that the stallion mourning in the centre of the panel is identical with the figure seated at the left stop, where he retains his horse'southward head and hooves."[41]

The Penance of Rhiannon? [edit]

Rhiannon riding in Arbeth, from The Mabinogion, translated by Charlotte Guest, 1877

Ute Schwab (2008), following Heiner Eichner (1991), interprets the left and key scenes on the correct panel as relating to the Welsh fable of Rhiannon. According to the Mabinogion, a medieval drove of ancient Welsh stories, Rhiannon was falsely accused of murdering and eating her infant son Pryderi, who, according to Schwab, is represented past the swaddled infant in the central scene. As a penance, she was required, equally depicted in the scene on the left, "to sit down beside the equus caballus-block outside the gates of the court for seven years, offering to carry visitors up to the palace on her back, like a beast of brunt.... Rhiannon's horse-imagery and her bounty have led scholars to equate her with the Celtic horse-goddess Epona."[42]

Satan and the Nativity? [edit]

![]()

Austin Simmons (2010) parses the frame inscription into the following segments:

- herh os-sitæþ on hærm-bergæ

- agl drigiþ swæ hiri er tae-gi-sgraf

- sær-den sorgæ and sefa-tornæ

This he translates, "The idol sits far off on the dire hill, suffers abasement in sorrow and centre-rage every bit the den of pain had ordained for information technology." Linguistically, the segment os- represents the verbal prefix oþ- assimilated to the following sibilant, while in the b-poesy of the second line er "before" is an contained give-and-take before a three-member exact compound, tae-gi-sgraf. The first member tae- is a rare form of the particle-prefix to-.[43]

The inscription refers specifically to the scene on the left terminate of the casket's right side. Co-ordinate to Simmons, the 'idol' (herh) is Satan in the grade of an ass, existence tortured by a personified Hell in helmet. The scene is a reference to the apocryphon Decensus advertizement Inferos, a popular medieval text translated into Anglo-Saxon. In ane version of the story of the Harrowing of Hell, a personified Hell blames Satan for having brought near the Crucifixion, which has allowed Christ to descend to Hell's kingdom and free the imprisoned souls. Therefore, Hell tortures Satan in retribution. Simmons separates the other scenes on the right side and interprets them equally depictions of the Nativity and the Passion.[44]

Runological and numerological considerations [edit]

The inscription "Fisc Flodu …" on the front of the Franks Catafalque alliterates on the F-rune ᚠ feoh, which connotes wealth or treasure

Each Anglo-Saxon runic letter had an acrophonic Old English proper name, which gave the rune itself the connotations of the proper name, as described in the Old English rune verse form. The inscriptions on the Franks Catafalque are alliterative verse, and so requite detail emphasis to i or more runes on each side. According to Becker (1973, 2002), these tell a story corresponding to the illustrations, with each of the scenes emblematic of a certain menses of the life and afterlife of a warrior-rex: The forepart inscription alliterates on both the F-rune ᚠ feoh (wealth) and the G-rune ᚷ gyfu (gift), respective to the jewellery produced by the goldsmith Welund and the gifts of the three Magi. "In this box our warrior hoarded his treasure, golden rings and bands and bracelets, jewellery he had received from his lord, … which he passed to his own retainers… This is feohgift, a gift non only for the go along of this or that follower, simply also to honour him in front of his comrade-in-arms in the hall."[45] The Romulus and Remus inscription alliterates on the R-rune ᚱ rad (journey or ride), evoking both how far from home the twins had journeyed and the possessor's call to arms. The Titus side stresses the T-rune ᛏ Tiw (the Anglo-Saxon god of victory), documenting that the peak of a warrior-rex'due south life is glory won by victory over his enemies. The correct side alliterates first on the H-rune ᚻ hagal (hail storm or misfortune) and then on the South-rune ᛋ sigel (sun, light, life), and illustrates the hero's death and ultimate salvation, according to Becker.

Becker also presents a numerological analysis of the inscriptions, finding 72 = 3 ten 24 signs on the front end and left panels, and a full of 288 or 12 x 24 signs on the entire catafalque. All these numbers are multiples of 24 = iii x viii, the magical number of runes in the elder futhark, the early continental runic alphabet preserved within the extended Anglo-Saxon futhorc. "In order to reach sure values the carver had to cull quite unusual word forms and ways of spelling which have kept generations of scholars busy."[46]

Osborn (1991a, 1991b) concurs that the rune counts of 72 are intentional. However, "whereas [Becker] sees this equally indicating pagan magic, I run into it equally complementing such magic, as another example of the Franks Casket artist adapting his heathen materials to a Christian evangelical purpose in the mode of interpretatio romana. The artist manipulates his runes very carefully, on the forepart of the casket supplementing their number with dots and on the correct side reducing their number with bindrunes, so that each of the iii inscriptions contains precisely seventy-two items.... The near obvious Christian association of the number lxx-two, for an Anglo-Saxon if not for us, is with the missionary disciples appointed by Christ in addition to the twelve apostles.... The number of these disciples is mentioned in scripture but in Luke ten, and there are two versions of this text; whereas the Protestant Bible says that Christ appointed a further seventy disciples, the Vulgate version known to the Anglo-Saxons specifies seventy-two. In commenting on that number, Bede assembly it with the mission to the Gentiles (that is, "all nations"), because seventy-two is the number of nations among the Gentiles, a multiple of the twelve tribes of Israel represented by the twelve apostles."[47]

Glossary [edit]

This is a glossary of the Sometime English words on the casket, excluding personal names. Definitions are selected from those in Clark Hall'due south dictionary.[48]

| Transliteration of runes on casket | Form normalised to Late Due west Saxon | Headword course (nominative atypical for substantives, infinitive for verbs) | Pregnant |

|---|---|---|---|

| agl[?] | āglǣc? | This word is a mystery, just ofttimes emended to āglǣc (neuter noun) | trouble, distress, oppression, misery, grief |

| ahof | āhōf | āhebban (potent verb) | lift upwards, stir up, raise, exalt, erect |

| and, stop | and | and (conjunction) | and |

| ban | bān | bān (neuter noun) | bone, tusk |

| bita | bita | bita (masculine noun) | biter, wild creature |

| den (occurring in the string særden) | denn | denn (neuter substantive) | den, lair, cave |

| dom | dōm | dōm (masculine substantive) | doom, judgment, ordeal, sentence; courtroom, tribunal, assembly |

| drigiþ | drīgeþ | drēogan (strong verb) | experience, suffer, endure, sustain, tolerate |

| oþlæ | ēðle | ēðel (masculine/neuter noun) | state, native land, home |

| fœddæ | fēdde | fēdan (weak verb) | feed, nourish, sustain, foster, bring up |

| fegtaþ | feohtaþ | feohtan (stiff verb) | fight, combat, strive |

| fergenberig | firgenberig | firgenbeorg (feminine noun) | mountain? |

| fisc | fisc | fisc (masculine substantive) | fish |

| flodu | flōd | flōd (masculine/neuter substantive) | mass of h2o, alluvion, wave; flow (of tide as opposed to ebb), tide, flux, electric current, stream |

| gasric | gāsrīc(?) | gāsrīc? (masculine noun) | fell person? |

| gibroðæra | gebrōðera | brōðor (masculine noun) | brother |

| gisgraf | gescræf | gescræf (neuter noun) | cave, cavern, pigsty, pit |

| giswom | geswam | geswimman (stiff verb) | swim, bladder |

| gisl | gīsl | gīsl (masculine noun) | hostage |

| greut | grēot | grēot (neuter noun) | grit, sand, earth |

| grorn | grorn | grorn (adjective) | deplorable, agitated |

| he | hē | hē (personal pronoun) | he |

| hærmberge | hearmbeorge | hearmbeorg (feminine noun) | grave? |

| herh (possibly occurring in the cord herhos) | hearg | hearg (masculine noun) | temple, altar, sanctuary, idol; grove? |

| her | hēr | hēr (adverb) | hither |

| hiæ | hīe | hē/hēo/þæt (personal pronoun) | he/she/it |

| hiri | rent | hēo (personal pronoun) | she |

| hronæs | hranes | hran (masculine noun) | whale |

| in | in | in (preposition) | in, into, upon, on, at, to, among |

| giuþeasu | Iūdēas | Iūdēas (masculine plural) | the Jews |

| on | on | on (preposition) | on, upon, on to, upward to, among; in, into, within |

| bone (possibly occurring in the string herhos) | ōs | ōs (masculine noun) | a divinity, god |

| romæcæstri | Rōmeceastre | Rōmeceaster (feminine noun) | the city of Rome |

| risci | risce | risc (feminine noun) | rush |

| sær (occurring in the string særden) | sār | sār (neuter noun) | bodily hurting, sickness; wound, sore, raw place; suffering, sorrow, disease |

| sefa | sefan | sefa (masculine substantive) | mind, spirit, agreement, centre |

| sitæþ | siteþ | sittan (strong verb) | sit, sit down down, recline |

| sorgæ | sorge | sorg (feminine noun) | sorrow, pain, grief, problem, care, distress, anxiety |

| swa | swā | swā (adverb) | so as, consequently, only as, so far every bit, in such wise, in this or that style, thus, and so that, provided that |

| tornæ | torne | torn (neuter noun) | anger, indignation; grief, misery, suffering, pain |

| twœgen | twēgen | twēgen (numeral) | 2 |

| unneg | unnēah | unnēah (adjective) | not nigh, far, away from |

| warþ | wearþ | weorðan (strong verb) | become |

| wudu | wudu | wudu (masculine noun) | wood, forest, grove |

| wylif | wylf | wylf (feminine noun) | she-wolf |

| þær | þǣr | þǣr (adverb) | in that location; where |

Encounter too [edit]

- Anglo-Saxon runes

- Former English rune poem

- Ruthwell Cantankerous

Notes [edit]

- ^ The beginning considerable publication, by George Stephens, Quondam-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England (1866–1901) I-2:470-76, 921-23, III:200-04, 4:xl-44, placed it in Northumbria and dated it to the 8th century. Although A. S. Napier (1901) concurs with an early on 8th-century Northumbrian origin, Mercia, and a 7th-century date, take also been proposed .[ citation needed ] The British Museum website (run into external links) says Northumbria and "first one-half of the 8th century AD", equally does Webster (2012a:92), "early office of the eighth century".

- ^ Vandersall summarises the previous scholarship equally at 1972 in setting the casket into an art-historical, rather than linguistic context. Mrs Leslie Webster, former Keeper at the British Museum and the leading expert, has published a new short book on the casket (Webster 2012b).

- ^ Webster (2000).

- ^ Parsons (1999, 98-100) has an important discussion on the runes used in the Franks Casket.

- ^ Webster (2012a:97); Ripon was suggested by Wood, who was able to connect Ripon with Brioude through the Frankish scholar Frithegod "active in both areas in the middle tenth century (Woods 1990, 4-v)" - Webster (1991) from BM collection database.

- ^ Vandersall 1972:24 annotation 1.

- ^ Webster (1991), from British Museum collection database

- ^ Measurements from British Museum Collections Database webpage. For date see notation to lead.

- ^ Webster (2012a:92).

- ^ Webster (1991); Webster (2012a:92); Webster (2012b:30-33).

- ^ Webster (2000).

- ^ Webster (2012a:96-97). (both quoted, in that order)

- ^ This scene was first explained by Sophus Bugge, in Stephens (1866-1901, Vol. I, p. lxix), as cited by Napier (1901, p. 368). See also Henderson (1971, p. 157).

- ^ Webster (1991)

- ^ Fletcher, R. The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386AD London 1997 pp269-270 ISBN 0002552035>

- ^ Hough and Corbett (2013: 106).

- ^ Page (1999, p. 175).

- ^ Another Anglo-Saxon bone plaque, existing only in a fragment at the Castle Museum, Norwich, which was found at Larling, Norfolk, also shows Romulus and Remus being suckled, with other animal ornamentation. (Wilson 1984, p. 86).

- ^ Neuman de Vegvar (1999, pp. 265–6)

- ^ Page (1999, pp. 176–7).

- ^ MacGregor, Arthur. Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn, Ashmolean Museum, 1984, ISBN 0-7099-3507-ii, ISBN 978-0-7099-3507-0, Google books

- ^ Napier (1901, p. 366), quoting Bugge in Stephens (1866-1901, vol. I, p. seventy).

- ^ British Museum Collections Database webpage, accessed January. 26, 2013; Webster (2012), p. 92

- ^ Osborn (1991b: 262-3). Psalm 90 in the Vulgate bible and Former English translation referenced by Osborn corresponds to Psalm 91 in Protestant and Hebrew bibles.

- ^ Cocco (2009: 30).

- ^ Page (1999, 178-9). Page's translations are endorsed by Webster (1999). See Napier (1901), Krause (1959), d'Ardenne (1966), and Peeters (1996) for discussion of culling readings.

- ^ Page (1999: 87)

- ^ Thomas A. Bredehoft, 'Three New Ambiguous Runes on the Franks Catafalque', Notes and Queries, 58.2 (2011), 181-83, doi:10.1093/notesj/gjr037.

- ^ Page (1999: 178).

- ^ Translation of H.A. Bellows, Oxford Univ. Press, 1926, as cited past Clark (1930, p. 339).

- ^ Clark (1930, p. 340)

- ^ Clark (1930, p. 342)

- ^ Clark (1930, pp. 352–iii).

- ^ Napier (1901: 379 n.ii). Napier (p. 364) reports that Dr. Söderberg of Lund had predictable Wadstein'south proposal already in the University, referring to a cursory mention in the Notes and News section of The Academy, A Weekly Review of Literature, Science and Art, August second 1890, p.90, col.i.

- ^ D'Ardenne independently put frontward Bouman's Hengist and Horsa reading, which she only discovered every bit her own commodity was going to press.

- ^ Becker (2000, unpaginated section "H-panel (Right Side) - The Motion picture").

- ^ Peeters (1996: 29), citing Daniel five:21.

- ^ Peeters (1996: 31).

- ^ Schneider (1959) similarly identified the right panel with Saxo's version of the death of Balder.

- ^ Howlett (1997: 280-1).

- ^ Howlett (1997: 281).

- ^ Green (1993, p. 30).

- ^ Simmons (2010).

- ^ Simmons (2010).

- ^ Becker (2002, unpaginated, section The Casket – a Warrior's Life)

- ^ Becker (2002), unpaginated department F-console (Front) - Number and value of the runes.

- ^ Osborn (1991b: 260-1). Howlett (1997: 283) concurs with Becker and Osborn that "The carver counted his characters."

- ^ John R. Clark Hall, A Concise Anglo-Saxon Lexicon, 4th rev. edn past Herbet D. Meritt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960); 1916 2nd edn available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/31543/31543-0.txt.

References [edit]

- d'Ardenne, Simonne R.T.O., "Does the right side of the Franks Casket represent the burying of Sigurd?" Études Germaniques, 21 (1966), pp. 235–242.

- Becker, Alfred, Franks Casket: Zu den Bildern und Inschriften des Runenkästchens von Auzon. Regensburg, 1973.

- Becker, Alfred, Franks Casket website dated 2002, with English and German language versions.

- Becker, Alfred, Franks Casket; Das Runenkästchen von Auzon. Magie in Bildern, Runen und Zahlen'.' Berlin 2021, ISBN 978-3-7329-0738-0.

- Bouman, A.C., "The Franks Casket," Neophilologus 3 (1965): 241–9.

- Clark, Eleanor Grace, "The Right Side of the Franks Casket," Publications of the Modern Language Association 45 (1930): 339–353.

- Cocco, Gabriele, "The Bowman Who Takes the Lid off the Franks Catafalque.", Studi anglo-norreni in onore di John Southward. McKinnell, ed. 1000. E. Ruggerini. CUED Editrice, 2009.

- Eichner, Heiner, Zu Franks Catafalque/Rune Auzon, in Alfred Bammesbergen, ed., Old English Runes and their Continental Groundwork (= Altenglische Forschngen 217). Heidelberg, 1991, pp. 603–628.

- Elliott, Ralph W.V., Runes: An Introduction. Manchester University Press, 1959.

- Light-green, Miranda Jane, Celtic Myths. British Museum Press, 1993.

- Henderson, George, Early Medieval Fine art, 1972, rev. 1977, Penguin, pp. 156–158.

- Hough, Carole and John Corbett, Beginning Old English. Palgrave, 2013.

- Howlett, David R., British Books in Biblical Style. Dublin, Four Courts Printing, 1997.

- Krause, Wolfgang, "Erta, ein anglischer Gott", Die Sprache 5; Festschrift Havers (1959), 46–54.

- Napier, Arthur Due south., in An English Miscellany, in honor of Dr. F.J. Furnivall, Oxford, 1901.

- Neuman de Vegvar, Carol Fifty. "The Travelling Twins: Romulus and Remus in Anglo-Saxon England." Ch. 21 in Jane Hawkes and Susan Mills, eds., Northumbria'due south Golden Historic period, Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill Thrupp, Strand, Gloucestershire, 1999, pp. 256–267.

- Osborn, Marijane. "The Seventy-Two Gentiles and the Theme of the Franks Casket." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen: Bulletin de la Société Néophilologique/ Bulletin of the Mod Language Lodge 92 (1991a): 281–288.

- Osborn, Marijane. "The Lid as Determination of the Syncretic Theme of the Franks Casket," in A. Bammesberger (ed.), Old English Runes and their Continental Background, Heidelberg 1991b, pp. 249–268.

- Page, R.I. An Introduction to English Runes, Woodbridge, 1999.

- Parsons, D. Recasting the Runes: the Reform of the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc (Runron 14), Uppsala 1999.

- Peeters, Leopold, "The Franks Casket: A Judeo-Christian Interpretation.", 1996, Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 46: 17–52.

- Schneider, Karl, "Zu den Inschriften und Bildern des Franks Catafalque und einer ae. Version des Mythos von Balders Tod." In Festschrift für Walther Fischer Heidelberg, Universitätsverlag, 1959.

- Schwab, Ute, Franks Casket: fünf Studien zum Runenkästchen von Auzon, ed. by Hasso C. Heiland. Vol. 15 of Studia medievalia septentrionalia, Vienna: Fassbaender, 2008.

- Simmons, Austin The Cipherment of the Franks Casket on Project Woruldhord, dated Jan. 2010.

- Söderberg, Sigurd, in London Academy, Aug. 2, 1899, p. 90. (As cited by Clark 1930)

- Stephens, George, The Sometime-Norse Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England (iv volumes), London: J.R. Smith, 1866–1901.

- Vandersall, Amy Fifty., "The Date and Provenance of the Franks Casket," Gesta xi, two (1972), pp. 9–26.

- Vandersall, Amy Fifty., "Homeric Myth in Early Medieval England: The Chapeau of the Franks Casket". Studies in Iconography 1 (1975): ii-37.

- Viëtor, W., "Allgemeinwissenschaftliches; Gelehrten-, Schrift-, Buch- und Bibliothekswesen." Deutsche Literaturzeitung. Vol. 25, xiii February. 1904.

- Wadstein, Elis (1900), "The Clermont Runic Casket," Skrifter utgifna af One thousand. Humanistiska Vetenskaps-Samfundet i Upsala 6 (7). Uppsala, Almqvist & Wicksells Boktryckeri A. B. Available every bit undated University of Michigan Libraries reprint.

- Webster, Leslie (1991), "The Franks Casket," in Fifty. Webster - J. Backhouse (eds), The Making of England: Anglo-Saxon Art and Civilisation, Advertising 600-900, London 1991, pp. 101–103 (text on British Museum collection database).

- Webster, Leslie (2000), The Franks Casket, pp. 194–195, The Blackwell encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Editors: Michael Lapidge, John Blair, Simon Keynes), Wiley-Blackwell, 2000, ISBN 0-631-22492-0, ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Webster, Leslie (2012a), Anglo-Saxon Art, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714128092.

- Webster, Leslie (2012b), The Franks Casket: Objects in Focus, British Museum Press, 2012b, ISBN 0-7141-2818-10, 9780714128184.

- Wilson, David M.; Anglo-Saxon Fine art: From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest, Thames and Hudson (The states edn. Overlook Printing), 1984.

- Wood, Ian N., "Ripon, Francia and the Franks Catafalque in the Early on Center Ages", Northern History, 26 (1990), pp. 1–xix.

Literature [edit]

- Richard Abels, "What Has Weland to Do with Christ? The Franks Catafalque and the Acculturation of Christianity in Early Anglo-Saxon England." Speculum 84, no. 3 (July 2009), 549–581.

- Alfred Becker, Franks Casket Revisited," Asterisk, A Quarterly Journal of Historical English Studies, 12/2 (2003), 83-128.

- Alfred Becker, The Virgin and the Vamp," Asterisk, A Quarterly Journal of Historical English Studies, 12/4 (2003), 201-209.

- Alfred Becker, A Magic Spell "powered by" a Lunisolar Calendar," Asterisk, A Quarterly Journal of Historical English language Studies, 15 (2006), 55 -73.

- M. Clunies Ross, A suggested Interpretation of the Scene depicted on the Right-Hand Side of the Franks Casket, Medieval Archaeology 14 (1970), pp. 148–152.

- Jane Hawkes and Susan Mills (editors), Northumbria's Aureate Age (1999); with articles by L. Webster, James Lang, C. Neuman de Vegvar on various aspects of the catafalque.

- W. Krogmann, "Dice Verse vom Wal auf dem Runenkästchen von Auzon," Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift, N.F. nine (1959), pp. 88–94.

- J. Lang, "The Imagery of the Franks Casket: Some other Arroyo," in J. Hawkes & South. Mills (ed.) Northumbria's Aureate Historic period (1999) pp. 247 – 255

- K. Malone, "The Franks Casket and the Date of Widsith," in A.H. Orrick (ed.), Nordica et Anglica, Studies in Honor of Stefán Einarsson, The Hague 1968, pp. ten–xviii.

- Th. Müller-Braband, Studien zum Runenkästchen von Auzon und zum Schiffsgrab von Sutton Hoo; Göppinger Arbeiten zur Germanistik 728 (2005)

- K. Osborn, "The Grammer of the Inscription on the Franks Casket, right Side," Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 73 (1972), pp. 663–671.

- M. Osborn, The Pic-Poem on the Front of the Franks Catafalque, Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 75 (1974), pp. fifty–65.

- P. Westward. Souers, "The Top of the Franks Casket," Harvard Studies and Notes in Philology and Literature, 17 (1935), pp. 163–179.

- P. Due west. Souers, "The Franks Catafalque: Left Side," Harvard Studies and Notes in Philology and Literature, 18 (1936), pp. 199–209.

- P. W. Souers, "The Magi on the Franks Casket," Harvard Studies and Notes in Philology and Literature, 19 (1937), pp. 249–254.

- P. W. Souers, "The Wayland Scene on the Franks Casket," Speculum xviii (1943), pp. 104–111.

- M. Spiess, "Das angelsächsische Runenkästchen (die Seite mit der Hos-Inschrift)," in Josef Strzygowski-Festschrift, Klagenfurt 1932, pp. 160–168.

- Fifty. Webster, "The Iconographic Programme of the Franks Casket," in J. Hawkes & Due south. Mills (ed.) Northumbria'due south Golden Age (1999), pp. 227 – 246

- L. Webster, "Stylistic Aspects of the Franks Casket," in R. Farrell (ed.), The Vikings, London 1982, pp. xx–31.

- A. Wolf, "Franks Catafalque in literarhistorischer Sicht," Frühmittelalterliche Studien 3 (1969), pp. 227–243.

External links [edit]

- Archaeosoup Productions, In Focus: Franks Catafalque. Posted 25 Aug. 2012.

- Boulton, Meg, Because the institutional narratives and object narratives of the Franks Casket, public lecture at the University of York, Feb. 3, 2015.

- British Library, The Franks Catafalque.

- British Museum, The Franks Casket / The Auzon Casket

- British Library, U.k. Web Archive Franks Casket, preserving Alfred Becker'south website.

- Drout, Michael D. C., 'The Franks Casket', Anglo-Saxon Aloud (15 February 2008) (readings of the poems on the front and right-hand panels).

- Foys, Martin, The Franks Casket: a Digital Edition', Edition of the runic inscriptions, with high-resolution images of each side of the object.

- Ramirez, Janina, Treasures of the Anglo Saxons. BBC Four production beginning broadcast 10 Aug. 2010. Office iii of 4 discusses the Franks Casket and the Welund legend.

- Ramirez, Janina, "The Franks Casket - with Tony Robinson". Podcast in acast Art Detective series. Published Feb. 22, 2017.

- West, Andrew, Anglo-Saxon Runic fonts.

- W, Andrew, Runic Text on the Franks Casket.

- Wright, Andrew [Deor Reader], Horsing Around? — Thorny Trouble of the Franks Casket Reveals Another Riddle, Dec. 23, 2017. Proposes an alternative reading of the right side.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franks_Casket

0 Response to "The Franks Casket Right Side Again"

Postar um comentário